This is a continuation of a prior editorial. If you haven't read it, I highly suggest reading it here.

For those unaware, Community was a sitcom set in a community college that centred on a cast of diverse and distinct characters that would in time play upon known genre traits and homages to create highly amusing entertainment, and despite its smaller viewing figures managing to build a massive cult following that allowed it to reach its coveted six seasons goal (the movie portion is yet to materialise). The Russo brothers were a key part of the show’s first three seasons, with executive producer roles and regularly taking turns in directing some of the series’ most beloved episodes; the most notable in this case being the season two finale ‘A Fistful of Paintballs/For a Few Paintballs More’. A sequel to the prior season’s infamous ‘Modern Warfare’ (directed by Fast and Furious director Justin Lin of all people), this finale had to not only be a worthy successor to the first season’s big hit but also make for a satisfying conclusion for the series arc regarding Pierce Hawthorne’s (Chevy Chase) decline in tolerability within his study group.

The solution? Tell two different stories within the confines of an overarching narrative, and in turn play with genre conventions to distinguish the two apart more so. ‘A Fistful of Bullets’ relies heavily on the Western aesthetic and focuses on a splintered collection of characters manipulated into going against each other, largely unaware of the competing force that’s pulling the strings (now that I’ve typed that out, it sounds awfully similar to Captain America: Civil War, another Russo project); in contrast ‘For a Few Paintballs More’ goes for a Star Wars spin as a band of misfits team up to take on the large conglomerate force (complete with white plastic armoured soldiers with no distinction from one another) and ultimately win. The whole thing is tied together by the whole paintball angle and Pierce’s involvement – at first blissfully unaware of his friends’ disdain for him but willing to himself manipulate them for the sake of aggravating the group’s de facto leader Jeff (Joel McHale), and later (upon being informed that he had lost his friends’ support) is willing to humiliate and sell out Jeff to the enemy in favour for his continued survival and pots of pudding. It’s only when Dean Spreck (Jordan Black) wonders why it took so long for him to be kicked out of the group that Pierce realise that he’s not how he perceives himself to be and becomes the bigger man; completing the Star Wars homage by disguising himself as one of City College’s men, taking out the last of the enemy and donating the prize money to Greendale. He understands he’s a difficult person to be with, and refuses the opportunity to still be a part of his group in favour of his own self-reflection and their happiness, thus concluding the season arc.

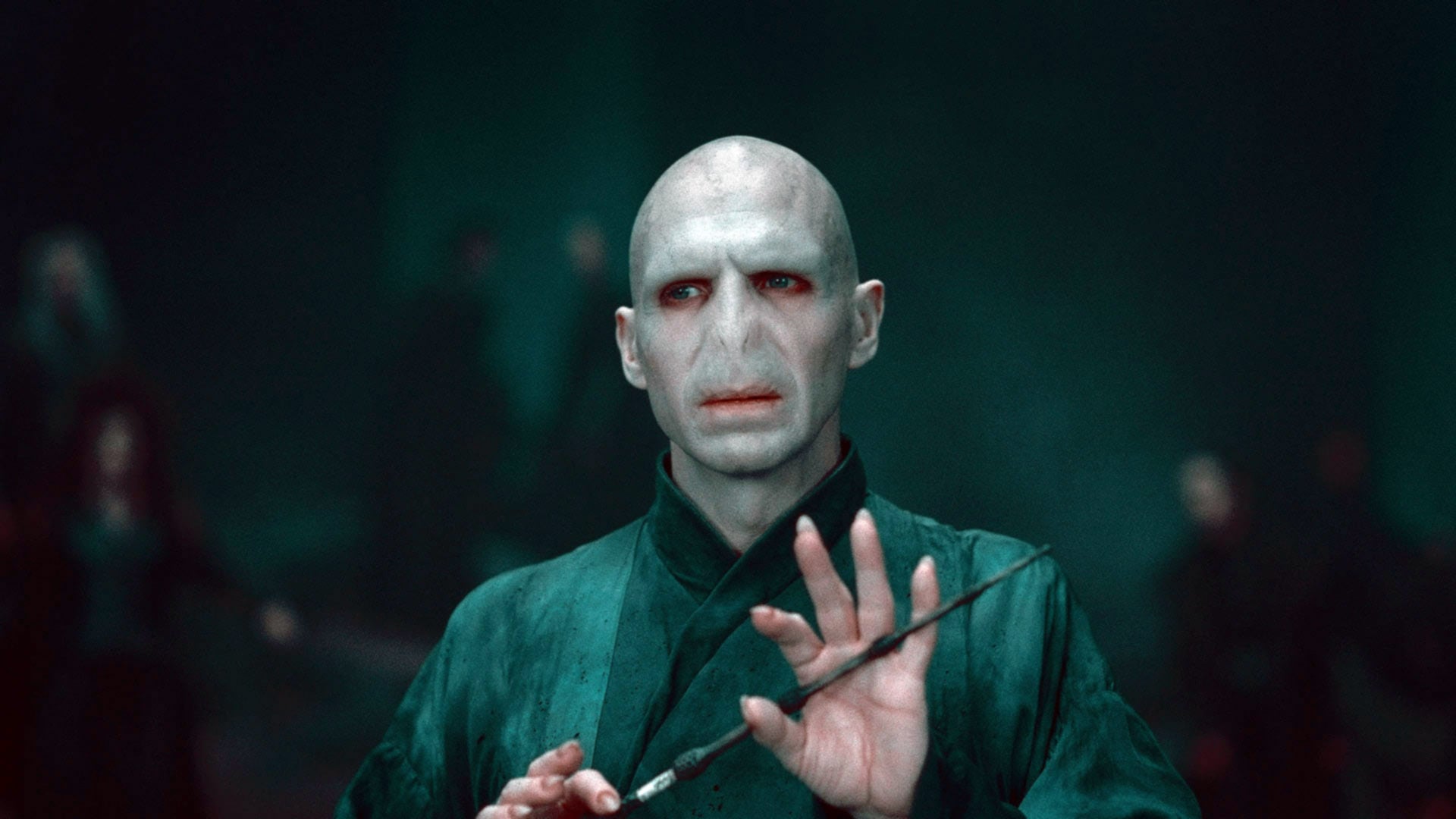

What really helps the recent Avengers entries is that they aren’t married to their source material as much as the likes of Harry Potter and Twilight are. Yes, it’s telling the story first realised in the comics, but thanks to the nature of the prior movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe it can branch out and present what’s overall a different story. The examples I mentioned previously, with the exception of Fantastic Beasts, all have to find a moment that they have to stop on more for the sake of the runtime than if it’s a good moment to stop. Case and point, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey: it ends following a fight with some prevalent orcs (of which they will repeatedly face over the next two films, and this fight isn’t even their first encounter), a character’s near-death, and the main character’s not even arriving where they need to be. The second entry, The Desolation of Smaug, has a better cliffhanger with the titular dragon’s flight towards the local town with the plan to eradicate it, but the final film quickly pushes aside the dragon within the first 30 minutes, thus making the year-long wait a letdown. Even Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows had a similar issue, with Part One ending on the death of a character who – while a fan favourite – hadn’t been seen in the films for close to a decade and Voldemort getting his hands on the Elder Wand. It’s an important moment, but considering we were only introduced to what the Deathly Hallows are not long beforehand it doesn’t have quite the same impact as it expects.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of how much time we’ve spent with these beloved characters that plays its hand in how much time we want to spend with their goodbyes. As mentioned in the first half, we watched the cast of Harry Potter grow up right before our eyes and wanted to see their decade-long journey would come to an end. Likewise, the last Avengers entries marked the conclusion to a decade-long story arc while also saying goodbyes to the likes of Robert Downey Jr., Chris Evans and (in-universe) Scarlett Johansson – all actors who made their start in the early years of the series and have been regular stars of these movies (unless he makes a cameo in Black Widow, next year will be the first year without a Chris Evans appearance in an MCU movie). It did also have the benefit of bringing in all the new heroes that were introduced across phases two and three – most notably the Guardians of the Galaxy, who had been separated from the Earth-bound events save for a Collector appearance in Thor: The Dark World – but it was a goodbye nonetheless, and a heartfelt one at that. All the other franchises were mere trilogies, quadrilogies and quintologies that came out on a yearly basis and lacked that attachment that most mainstream audiences had for the big two series. Sure, they had their fanbases, but fanbases alone don’t lead to big lasting success, and in turn loyalty to those fanbases and properties are vital in keeping interest alive. After all, had J.K. Rowling not gone on retconning tirades with bizarre notions like wizards defecating themselves or opted not to stand by the controversial casting of Johnny Depp, would the last Fantastic Beasts entry have been more successful instead of souring the goodwill that had kept her brand alive these past two decades

It’s very possible we aren’t going to get an event quite like Avengers: Infinity War/Endgame again. Say what you will about the quality of either entry, there’s no denying just how much of the media landscape was centred around speculation and reaction for them both, and how they’ve reaped the rewards for an earned finale (even if it isn’t really a true finale for the franchise). Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was the closest thing to that level of event cinema in its day, and while such levels of hype was usurped over time with the likes of the first Avengers outing and the return of Star Wars in 2015, there’s no denying that film didn’t leave a strong mark on Hollywood. It’s just a mark that was polished and made bigger by the Avengers and two men who knew what they were doing thanks to experience doing a little show on NBC. I don’t know about you, but I think that’s “streets ahead”.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of how much time we’ve spent with these beloved characters that plays its hand in how much time we want to spend with their goodbyes. As mentioned in the first half, we watched the cast of Harry Potter grow up right before our eyes and wanted to see their decade-long journey would come to an end. Likewise, the last Avengers entries marked the conclusion to a decade-long story arc while also saying goodbyes to the likes of Robert Downey Jr., Chris Evans and (in-universe) Scarlett Johansson – all actors who made their start in the early years of the series and have been regular stars of these movies (unless he makes a cameo in Black Widow, next year will be the first year without a Chris Evans appearance in an MCU movie). It did also have the benefit of bringing in all the new heroes that were introduced across phases two and three – most notably the Guardians of the Galaxy, who had been separated from the Earth-bound events save for a Collector appearance in Thor: The Dark World – but it was a goodbye nonetheless, and a heartfelt one at that. All the other franchises were mere trilogies, quadrilogies and quintologies that came out on a yearly basis and lacked that attachment that most mainstream audiences had for the big two series. Sure, they had their fanbases, but fanbases alone don’t lead to big lasting success, and in turn loyalty to those fanbases and properties are vital in keeping interest alive. After all, had J.K. Rowling not gone on retconning tirades with bizarre notions like wizards defecating themselves or opted not to stand by the controversial casting of Johnny Depp, would the last Fantastic Beasts entry have been more successful instead of souring the goodwill that had kept her brand alive these past two decades

It’s very possible we aren’t going to get an event quite like Avengers: Infinity War/Endgame again. Say what you will about the quality of either entry, there’s no denying just how much of the media landscape was centred around speculation and reaction for them both, and how they’ve reaped the rewards for an earned finale (even if it isn’t really a true finale for the franchise). Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was the closest thing to that level of event cinema in its day, and while such levels of hype was usurped over time with the likes of the first Avengers outing and the return of Star Wars in 2015, there’s no denying that film didn’t leave a strong mark on Hollywood. It’s just a mark that was polished and made bigger by the Avengers and two men who knew what they were doing thanks to experience doing a little show on NBC. I don’t know about you, but I think that’s “streets ahead”.